Please see the link to our secure website order form page, shown below. We love doing these ruminations on books and making our suggested lists of important titles, but, of course, we make our living selling the books. Thanks for your consideration. Happy book buying, and happy reading!

For

For

this Fourth of July holiday weekend, I want to tell you about a book that I

very much enjoyed, one that I can say even deeply moved me. There are layers of

complicated backstory around the topic of the book that I mostly won’t go into, but you should know that I

found this book to be a surprisingly gripping read for me.

I like the author’s

previous writing, enjoy reading about history, but have an allergy to books

about patriotism. I’ve reviewed books on the endlessly interesting history of the Founding Fathers

here at BookNotes before, and enjoy telling people about this genre about civic life, the common good, public

faith and the ideas and virtues that have given shape to our North American

culture, and our United States, particularly.

Oh

how I love the kind of patriotism that cares about a land and a place and a

country, honoring one’s own heritage and history – the good and the bad –

without necessarily demeaning others. These lines written by Lloyd Stone after

WW I, sung to the achingly gorgeous tune of Finlandia

always choke me up:

This

is my song, O God of all the nations,

a song of peace for lands afar and mine;

this is my home, the country where my heart is;

here are my hopes, my dreams, my holy shrine:

but other hearts in other lands are beating

with hopes and dreams as true and high as mine.

My country’s skies are bluer than the ocean,

and sunlight beams on cloverleaf and pine;

but other lands have sunlight too, and clover,

and skies are everywhere as blue as mine:

O hear my song, thou God of all the nations,

a song of peace for their land and for mine.

I

may not be in the majority, I am aware, although I know I am not alone, to say

I worry about over-stated patriotism, both the cheap kind where people with

flag-themed beer cozies think they are being honorable yelling slogans about

American being Number One or the kind that insists we must be strong in

military might and global influence as if we are an Empire that measures worth in sheer fire power.

I was raised in a very patriotic home –

my family has lost loved ones in wars. The three older men I care about most

(my father, my brother, and my father-in-law) all served in the military,

proudly, as officers. (See, I have this reflex to say that because in my

experience to say one is critical of unadulterated patriotism will surely be

criticized, as if I don’t care about vets. I don’t know anyone who “blames

America first” or fits the description of an “America hater” but so many right

wing talk show hosts and conservative pundits tar us all with that inaccurate

accusation. It offends me. Do you know what I mean?)

So,

in part because of my own father’s wisdom as a good conservative, I came to believe that too much misguided and

uncritical patriotism is inappropriate, foolhardy, even, especially for Christians. To use the language of Saint Augustine,

perhaps channeled afresh through Davey Naugle’s beautiful Reordered Love, Reordered Lives or James K.A. Smith’s must-read

You Are What You Love, it is

distorted affection and perhaps idolatrous to love a government too much, or in

the wrong way. We should give all things their due and love the right things to

a proper degree, and each thing properly; love of state isn’t a bad thing, and

the Bible calls us to honor the proper authorities. In a good

world, at least, it would be disordered not

to love your land and government, somewhat, somehow.

The

mindless saying “My Country Right or Wrong” suggesting that one dare not

criticize one’s own land was not promoted in my Christian home, but it was in

the air everywhere in the late 60s and 70s when I was coming of age and

thinking about politics, citizenship and the role of protest (in the Bible and

in contemporary society.) Large

matters of public policy (the Viet Nam war, the nuclear arms race, America’s

role in propping up corrupt regimes from the Philippines to Iran to nearly

every oppressive banana republic in Central America) were being debated. I cannot tell you how many times I was

told I should move to communist Russia for daring to say that my beloved land

was doing evil in the Third world, or that we had issues like race and poverty

and justice for migrant workers or corporate shysters polluting our air and

water without consequence to deal with here at home. Those stupid replies to legitimate social criticism still

weigh heavy on my heart, decades later.

Civil religion became the phrase scholars used to

Civil religion became the phrase scholars used to

explain the nearly religious way faith in one’s own government, with no

tolerance for critique, functions. Again, think of James K.A. Smith’s analysis

of “cultural liturgies” in You Are What

You Love. Hand over heart pledges of allegiance and using Bible language of

heaven (“alabaster cities gleam, untouched by human tears”) to describe any temporal

nation should give us pause. It is dangerous to allow the faith of the church to be used as window dressing for the secular state.

I shouldn’t have to remind you that this

kind of story of our own country as called and exceptional and somehow nearer

to God than others is commonplace, but for Biblical people, unacceptable. Biblical scholars and some brave

pastors use the analysis of civil religion as they draw upon the Old Testament

prophets who offered solemn rebuke to ancient Israel when the injustices of the

land were legitimized by implying God was on their side, no matter what. “The

temple of the Lord, the temple of the Lord” they would chant, and Jeremiah, for

one, would insist that even God’s covenant people couldn’t get away with murder

by claiming to be exceptional. Every

nation will be judged by the sovereign of history, and no nation should be

loved inordinately; patriotic sentiment or national loyalty ought never to allow

us to overlook injustices or a lack of public righteousness. We must be careful

that care for our nation doesn’t turn into the idol of nationalism. Pride still goeth before a fall.

In

Jeremiah 22 the prophet extolled a former king for doing justice and taking the

side of the oppressed and hurting; liberal justice advocacy for the powerless

caused it to be “well” with him and indicated authentic spirituality (“for is

that not what it means to know me, says the Lord” v.16.)

Then the prophet bluntly condemned the new king for building

Then the prophet bluntly condemned the new king for building

a fancy palace without paying fair wages, for living high on the hog and

thinking his legitimacy was based on his profitable international business

dealings (see v. 14-15a, although the NIV misses the market aspect of it, “competing in Cedar.”) Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, take note! It isn’t the point of this column to

document the vast amount of Biblical material that calls us to be critical of

our own beloved land and to resist civil religion, but it is important to at

least recall the dangers of quasi-religious, overly sentimental and uncritical

faith in one’s own country, or its founding mythologies, a sin that is as old as Sodom and Gomorrah (see

Isaiah 1: 10-17 or Ezekiel 16:49 to see how the prophets used the economic injustice

in those cities as emblematic of the sins of Israel) and as recent as any

belligerent political debate where U-S-A, U-S-A becomes a chant for greatness, without

proper humility.

I

say all of this on the fourth of July, to tell you that I am not one

who generally likes the “God Bless America” cantatas or other

red-white-and-blue celebrations that seem to me to smack of civil

religion. I detest “my country

right or wrong” thinking and I believe, generally speaking, we have too much

patriotism, or at least too much that isn’t critically engaged in the realities

of both the true goodness and evident evil of our blessed but broken land.

And,

And,

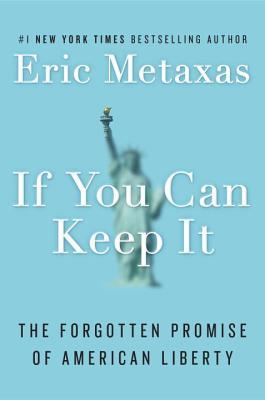

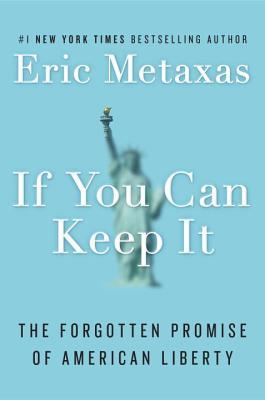

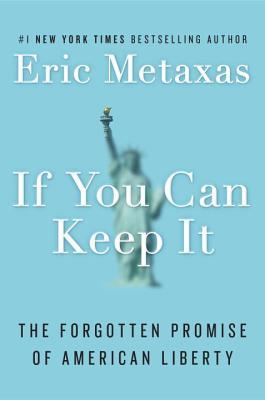

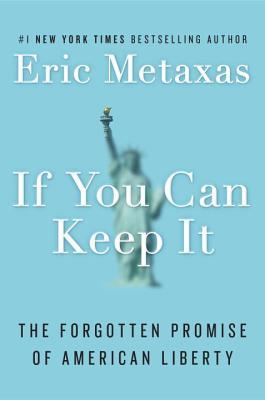

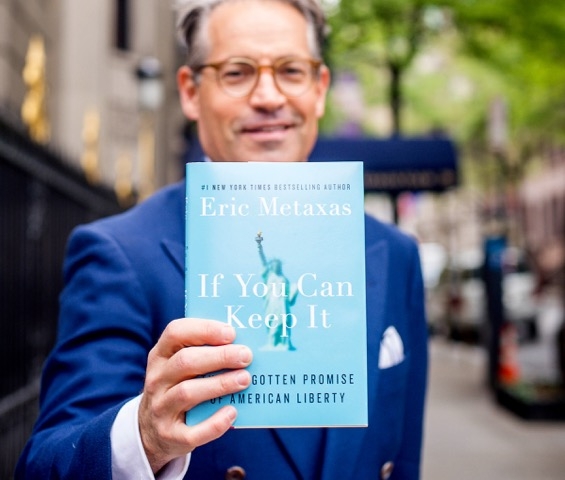

then, yet — surprise — to say this: I loved Eric Metaxas’s new book If You Can Keep It: The Forgotten Powers of

American Liberty (Viking; $26.00; 20% off sale price = $20.80.) Mr. Metaxas is a born storyteller, a

great communicator, and a fine writer. I was worried about this book, to be

honest (see the aforementioned fear of civil religion and my concern as a

Biblical person that no one nation should be honored with religious-sounding

absolutes which closes off an possibility of critique and repentance.)

But,

despite a few small quibbles, I loved it. And I commend it to those who, like

me, maybe wouldn’t be apt to pick it up.

Really, you should send us an order for this book – it’s a great read, even if you want to push back on some points. It’s a great time to read such a book.

I

suppose many of you don’t resonate with my concerns about misguided patriotism.

You might be quite likely to buy this book and we would be delighted if you

You might be quite likely to buy this book and we would be delighted if you

ordered it from us. I don’t have to convince you that Eric is an amazingly

sharp guy, a talk show host and pundit who seems to bring the wit and depth

(well, almost) of a William F. Buckley and the gritty evangelical faith of

Chuck Colson, and the interest in talking to intellectuals and thought-leaders

about big questions as might, say, Os Guinness or Nancy Pearcey. Eric is a gifted writer, a funny,

funny, guy, and agree or not with all of his views (or like his jokes)

expressed on his daily radio show, he is an author I suspect you appreciate.

If

If

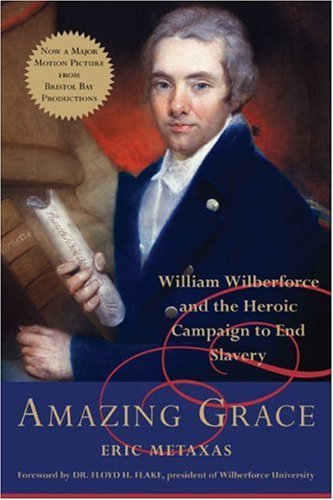

you read even somewhat in conservative evangelical circles, you know his

wonderfully-written and fascinating Bonhoeffer biography (Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy) and his best-selling book

about William Wilberforce, Amazing Grace:

William Wilberforce and the Heroic Campaign to End Slavery from which they

made the must-see, very moving film of the same title.

I hope you  know his great pair of recent paperbacks,

know his great pair of recent paperbacks,

Seven Men:

The Secret of Their Greatness and

The Secret of Their Greatness and

Seven Women: The Secret of Their Greatness.

He has a real knack for getting important things said by way of telling the

tales of historical figures.

Without being didactic about it, he allows pretty conservative values

and political tendencies to bubble up naturally as he tells us about this

courageous freedom fighter or that justice advocate or that

culturally-important poet or leader, telling us about folks from Jackie

Robinson to Hannah More, from Mother Theresa to Eric Lidell. If you’ve read his

books, you know he’s got a knack for this and that his books are enjoyable and

informative.

It

It

is the readers who might not want to read Eric Metaxas, or who aren’t drawn

to read about the Founding Fathers, that I want to persuade to consider giving If You Can Keep It a try. It is a fast-paced book, serious but

not dense, and, as I’ve said, I enjoyed it very, very much. Like reading David McCullough’s

1776 or watching the TV adaptation of

John Adams, it properly shamed me a

bit, making me ask myself why I am reluctant to be clear about my appreciation

of American ideals and the principles at the heart of the Republic. There

really was a lot in here that I learned and a lot that made me feel some things

pretty deeply. I hope you’ll

appreciate my remarks about it; they are heart felt, and writing this out is

better for me than grilling hot dogs on this national day of honoring a

brilliant revolution.

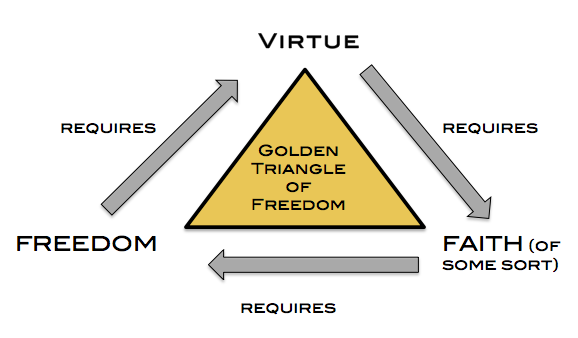

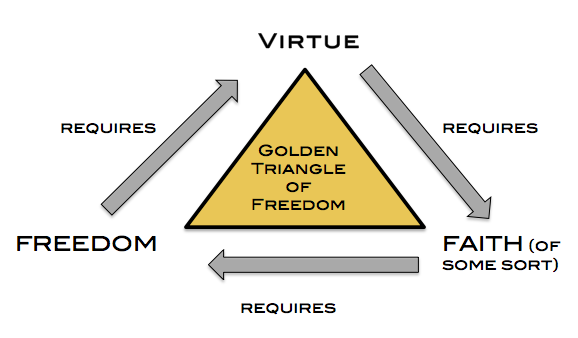

THE

GOLDEN TRIANGLE

If

you’ve read the books on civility and the public square by Os Guinness (most notably

A Free People’s Suicide: Sustainable Freedom and the American Future) one of the

central teachings of If You Can Keep It

will be familiar. Guinness has made explicit the three-fold flow of traits that

are central to keeping America vibrant and healthy.

There is the constitutional

assertion of freedom of and from religion that is a building block to American

culture. Religion, Metaxas reminds us, channeling Guinness’s own reading of the

framers and founders, must not be coerced. Only a freely chosen faith can be

sustainable and profound enough to guide and inform and bolster civil goodness

in the public square. So religious liberty was a huge matter, freedom of

conscience, for everyone, regardless of conviction. Ahh, but how does one

maintain such religious liberty? Only a truly religious people can step up and

live out such religious freedom (again: a coerced faith or state church or

civil religion simply won’t do.) So there is this significant interplay between

freedom of and from forced religion and a robust, lived faith that offers a

solid grounding for public virtue.

And,

as he makes clear, virtue is needed.

Otherwise, things fall apart.

This

is, by the way, one of the great insights in de Tocqueville, the mid-nineteenth century Frenchman who wrote his amazing memoir of his journey to and impressions

of America, called Democracy in

America. He wondered, a century after the great colonial revolution, how

the States were faring, what made America what it was. He famously found a deep

religiosity at the heart of the culture, everywhere he went. He concluded that

“liberty cannot be established without morality nor without faith.”

Ponder it a minute: if we are free to do what we want but we are not moral

people, then, inevitably, everyone will, in fact, do what they want — for

themselves, probably, disregarding the common good. The founders were seriously well-read in moral philosophy, and

somewhat in theology, and were deeply aware (more than any of our contemporary

public leaders) of a realistic perception about the nature of the human

person. The human condition is, among other things, that we are sinful, disordered, often selfish, and such an insight must inform how we think

about social arrangements and our view of power and the rule of law and political theory and the like. (Yes, too, the famous “checks and

balances.”) This is heavy stuff and the brilliant leaders of the Constitutional

Convention (sometimes called the Federal Convention) in the summer of 1787 were

serious thinkers, debating well this kind of thing. I suppose you know of The

Federalist Papers, written the following year, just for an example of the depth of their discourse, which Metaxas cites on occasion.

So

the question looms: what makes people want to be good, or at least good citizens, thinking of the

commonwealth over their own individual needs and wishes? Great sacrifice for

the commons comes from people who have a moral compass pointing them to care

about others, and, it seems almost empirically obvious, that this most naturally

happens when people are guided by a religious faith that teaches the golden

rule and the like.

So

So

there you have it, for starters, the bold claim that the Founding Fathers

presumed a certain sort of worldview, if you will, and at least three things that

they wrote about endlessly, but never quite so directly as when Guinness or

Metaxas spells it out as the “golden triangle.”

Freedom

Requires Virtue

Virtue

Requires Faith

Faith

Requires Freedom

Metaxas

notes that in recent years, this idea of the significance of faith and

religious liberty for our public life is virtually unheard, at least in intellectual circles, and

when it is, it is often dismissed if not mocked. The religious freedoms for mediating institutions and faith-based associations are woefully neglected (although Metaxas doesn’t write about contemporary policy or court rulings much regarding this up-to-the-week topic.) Regarding his own education (his degree is from Yale)

and the lack of awareness of the interplay of this necessary golden triangle of

freedom, virtue, and faith, he writes, “Virtually no one seemed to understand

what the founders had taken for granted as the secret center of their novel

idea of self-government…”

Or

as we might say today, the “secret sauce.”

Metaxas

continues,

If America was indeed a country created not

because of ethnic or tribal boundaries but instead because a people had come to

believe – and therefore embody – as a set of ideas, how could America be said

to exist if almost no one anymore knew what those ideas were? If these ideas

had essentially evaporated from our national consciousness for forty years or

more, weren’t we unwittingly but unavoidable becoming Americans in name only…

If You Can Keep It:

The Forgotten Powers of American Liberty draws easy-to-understand images,

is chock full of illustrations and stories and episodes, offers primary source

excerpts from speeches and letters, providing good summaries, (if a bit too

sweeping at times) and gives mostly very solid insights about the nature of the

ideas behind the Constitutional Convention and the framing of our founding documents.

His point is that these genius thinkers – Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, John

Adams, Ben Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, John Jay, and the others – despite

faults great and small – came up with a truly new and previously untried experiment

in self-government. This was a remarkably new idea, and they were deeply

committed to this new set of ideas, itself a remarkably new notion.

As

a matter of small detail, a number of these great thinkers who were deputies at

the convention did not sign the Constitution; Jefferson, whose influence was

significant, was in France. Some of the gentleman, such as George Mason, and

the interestingly named Catholic from Baltimore, Luther Martin, refused to sign

on principle. Some awaiting a “Bill of Rights.” Some had just gone home or fell ill.

Seeds

that were sown through the centuries were taken up from the Greeks and Romans,

through the Magna Carta, the Enlightenment, the Protestant reformation and the

British revolutions, but no-where on the planet, ever, did anyone every come up

with such audacious claims, and make such a bold and daring move to create a

Republic such as ours.

I

know this is often said, but it is nearly breathtaking to read of it again, and

in Metaxas’s hands, the radical and daring nature of this project (less, it

seems, the Declaration of Independence, itself amazing, and the revolt from the

King, dramatic as that was, but more so the new ideas to create a new form of

government, rejecting monarchs or kings out of a whole new paradigm, so to

speak) is utterly exciting. This book should be used in high school civics

classes and study groups from sea to shining sea!

I

could quote page after inspiring page of Metaxas writing about this stuff, but

if you are a history buff, I don’t have to tell you — these eighteenth century revolutionaries were brilliant and eloquent, and even the small bits of

their writings offered here are fabulous to read and ponder. I appreciate how Metaxas not only quotes

them liberally but gives background and color, as a fine storyteller and

popularizer should.

I

appreciate how he surveys how old-timers have written about these assertions;

his long and important chapter on the brilliance of the best Longfellow poem

(on Paul Revere) and how it was written for deep social purposes on the eve of

the Civil War, drawing on a sense of unity and the common good from the

Revolutionary era, was tremendous!

VENERATING HEROES

He

has a chapter called “Venerating Our Heroes” which I thought was fabulous – I

didn’t know much about Nathan Hale, that’s for sure. I would want to add a few other heroes that Eric might not,

but his vision (or is it a strategy?) to keep virtue alive by telling the

stories of virtuous leaders, is so, so necessary. (It is, by the way, the

project behind his Seven Men and Seven Women books, each showing the “secret

to their greatness” as a heroic sort of courage and integrity.) There is a lot to think about in this

chapter, and it strikes me as urgent in our age of anti-heroes and sex-driven consumerism.

(When will we grow tired of Kim Kardashians’ boobs or Beyoncé’s butt? And how

bad has it gotten when even fundamentalist spokespeople like Jerry Falwell, Jr.

happily pose giving a thumbs-up in front of Donald Trump and his framed Playboy cover?)

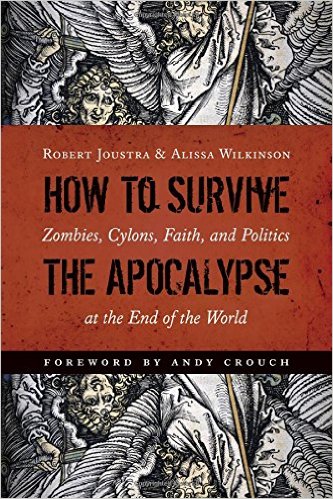

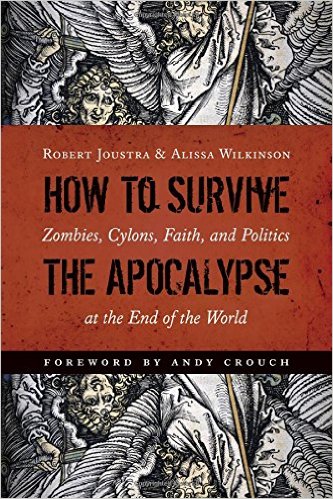

For

For

a more sophisticated treatment of the role of anti-heroes as an indication of

the gloomy secularized times, by the way, see the book I’ve been raving about in the

previous BookNotes posts, How To Survive the

Apocalypse: Zombies, Cylons, Faith, and Politics

at the End of the World by political theorist Robert Joustra and

film critic Alissa Wilkinson (Eerdmans; $16.00.) The point, again, is that

Metaxas reminds us in that good chapter about the role of virtue in leaders,

and the need to tell the stories of heroism, a practice that has fallen on hard times (amidst the coming zombie apocalypse and whatnot.)

He

reminds us that,

self-government entails far more than obeying

laws. Tocqueville refers to something he calls the “habits of the heart” and

the “mores” of the American people. He says that it is these things that are

really at the center of keeping our republic. Going to church and obeying laws

are important, but there are other things that also deserve to be mentioned and

examined as central to keeping our freedoms… we need to keep in mind that all of these things reinforce

one another. We cannot pretend that one or another of these alone is

sufficient. They are all part of a larger mind-set.

And

so, he looks at the notion of the heroic in general, and the specific practice

of venerating heroes. Again, I

think of Smith’s “cultural liturgies” project, thinking about the formative

influence of cultural practices; who and how we honor the heroic is

fascinating, and Metaxas invites us to think about that, from storytelling to

parades, from public statues to how history is taught.

(And, yes, he addresses fairly, if not with quite enough gusto for my tastes, the important matter of

hagiography, and of how to be honest about the large failings of past heroes.

He is blunt about that, saying, “of course it is true that people can venerate

heroes so much that they overlook important flaws” and he mentions, as

examples, JFK, St. Patrick, and of course (given his expertise and passion for

telling the tales of the abolitionists) the terrible irony that some of the

framers were themselves slave holders.

In any case, in latter decades we have swung so

far in the other direction that venerating heroes, which used to be part of our

common vocabulary, is no longer a language we speak or really understand. But

this has served to undermine the very idea of greatness and the idea of the heroic,

which is deeply destructive to any culture but especially to a free society

like ours, where aspiring to be like the heroes who have gone before us is a

large part of what makes citizens want to behave admirably. Denigrating heroes,

or simply failing to venerate them, has a cynical and toxic effect on the young

generation, and we have now had fifty years in which we have neglected this “habit

of the heart” so vital to our free way of life.

I

think he is on to something, don’t you?

PAMELA ANDERSON VIDEOS? REALLY?

Metaxas

further illustrates how moderns have treated these things more generally — our

views of liberty and such — sometimes with illustrations so vividly weird that

one doesn’t know whether to laugh or cry, as when Joy Behar, one of the hosts

of ABC’s The View suggested after

9-11 that we should resist the Taliban by dropping blow-up sex dolls and Pamela

Anderson videos over Afghanistan.

Yep, that’s it – notice: freedom is

most fundamentally understood as freedom from

restraints of any sort, and, in the contemporary hyper-modern culture, that is

most understood as freedom from sexual restraint. Eric notes, “It was a

classically Freudian idea of the problem at the center of human life, and as

far as she was concerned, that was what our American freedom existed to wipe

out.

He

continues:

This suggestion that raining pornography and sex

toys might pointedly express American freedom was an important and bracing

moment in television history, because the divide between the founder’s view of “liberty”

and the current misunderstanding of it had never before been more perfectly

contrasted. But what happened in the centuries since the ideas based on

Montesquieu and Locke and Jesus had devolved into what amounted to an

airdropped “kiss off” to the medieval coelacanths in their Afghani caves?

During previous wars we might have thought to drop Bibles or copies of our Constitution

because we knew that these contained the ideological dynamite to free those

cultures of their oppressive bindings.

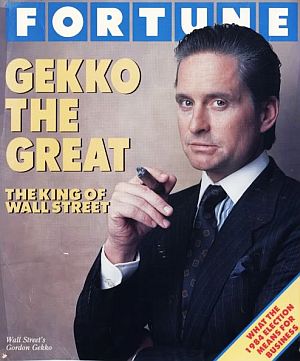

LIBERAL AND CONSERVATIVE MISUNDERSTANDINGS

It

is very interesting and helpful that Metaxas has good pages exploring this,

what he calls the “liberal” misunderstanding of freedom. We should pay heed of this somewhat philosophical question. But it is to his credit that he then

also has pages looking at what he terms a “conservative” misunderstanding of

freedom, where he is hard on the neo-con hopes that capitalism and economic

growth will naturally bring about renewal and liberty and justice for all. The free market, he notes, “delivers

what people want” and in that sense it is amoral, or at least deeply connected

to what the people stand for, shaped by the values and desires of the culture.

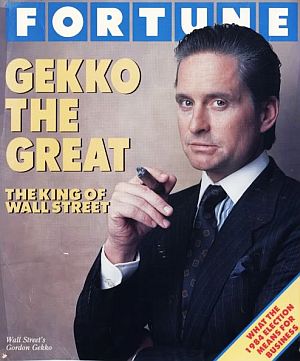

Listen

to him on this:

Neither in voting nor in finance is pure self-interest

Neither in voting nor in finance is pure self-interest

always in the best interest of the nation. You may recall Michael Douglas’s

character’s infamous statement in the movie Wall

Street. With his slick-back hair, Gordon Gekko declared, “Greed is good.”

In fact it is not. It’s not only not good, it is evil. But it is not only evil

and morally wrong, it will in the end lead to the debasement and destruction of

the free market, just as naked and selfish self interest in voting will lead to

the debasement and destruction of democratic government.

Metaxas

is clear about the problems with the typical liberal and typical conservative

tendencies and errors – and the “golden triangle” comes to the rescue. You see, the government cannot force us

to be good. As people made in God’s image with certain inherent dignity, we must

have freedom, but for freedom to be sustained, to allow a culture that is

healthy and a government “for” the people — the common good, as Catholics tend

to say — we need good people, who

will put common concerns above their own greed. And so we need religion to underscore morality, but we

cannot have authentic religion without religious freedom. It really is an endless, inter-related triangle.

What

this supposes is that we may not be able to sustain our ordered sense of

liberty, our structures for democratic freedom, for being a republic, given our current greeds and ideologies and markets. (Decades ago, Francis Schaeffer, a popularizer of intellectual history and a

wide-as-life worldview of Christ’s care for every square inch of His world,

predicted that by the early twenty-first century people may become so committed

to their own “personal peace and affluence” that they will permit a national

security state, accepting too much law and order to protect their own suburban

pleasures. Wow!)

THE STORY THAT GIVES US THE TITLE

So,

can we sustain our forms of government, our freedoms? Can we keep it?

As

you may know, there is a historical conversation from which the book gets its

title.

In

that summer of 1787, when those most brilliant men met to devise a new

constitution – cited for centuries later, by leaders from Lincoln to Martin

Luther King (who called it “a promissory note to which every American was to

fall heir”) to idealistic reformers all over the globe – they understood that “American

would not flourish without great help from all Americans.” We must take up that “promissory note”

and be good Americans.

That

is the key take-away from the book.

“Future

Americans depend on present-day Americans doing their duty in this,” Metaxas

writes, wisely.

(By

the way, this was part of my approach in a recent Op Ed piece in our local York

Sunday News paper criticizing a local knucklehead school board member making

gross anti-Muslim comments and harassing a church that was reaching out in

kindness to Muslim neighbors here in Dallastown. It was anti-American, I said,

to be so ugly about fellow citizens’ deepest beliefs, as if religious freedom

is not for all or as if the common courtesy of wishing another well is somehow

bad. I implied, sincerely, that this GOP delegate was a bad conservative and a

bad American.)

Can

we sustain the insight and virtue and freedoms dreamed about by the framers and

founders? Can we be good stewards of these ideas and practices that have been handed down over time?

So

do you know about the brief conversation between Benjamin Franklin and a Mrs.

Powell, as recorded by Dr. James McHenry, a delegate from Maryland, the last

day of the long, long convention in Philadelphia? Metaxas tells it well:

Benjamin Franklin was 81 that summer, described

by Metaxas as “the oldest delegate, the eminence

grise who for his part in those hallowed proceedings came to be known as

the “sage of the Constitution.” Franklin had by that time lived in Philadelphia

sixty four years since arriving there in 1723, aged seventeen, so for all we

know, he knew this now mythical and otherwise forgotten Mrs. Powell, who has

come to stand for all of American since that day when she spoke to Franklin in

a tone that seemed to bespeak some degree of familiarity.

According to McHenry, Mrs. Powell put her

question to Franklin direction: “Well, doctor,” she asked him, “what have we

got? A republic or a monarch?”

Franklin, who was rarely short of words or wit,

shot back: “A republic, madam – if you can keep it.”

Keeping

Keeping

American constitutional freedoms, through careful attention to sustainable

structures of freedom of religion and a robust, common-good sort of public

morality, bolstered by sincere, lively faith, is not the only thing Metaxas

writes about in If You Can Keep It. It

is a good, good start, and worth reading this summer even if you know a bit

about the Constitution and have interest in questions of public justice and

religious freedom and the like. (And it is important to read if you tend not to read much along those lines –

this is a lesson in patriotism unlike the simplistic and jingoistic stuff that

sometimes passes for civic lessons and may inspire some of the jaded among us

to take up this work of forging a healthy view of citizenship.)

Again,

I was struck by how vital all this feels while reading Metaxas’s energetic

writing — even when he overstates a few things. (He waxes eloquent noting how many

good things have come from the United States, listing inspirational stuff from

the invention of baseball and basketball to jazz to the invention of the

computer and the internet, saying these things were made possible by “that one

document written in that hot room in Philadelphia over the course of one

hundred days — that promise to

the future of the world.” Okay, so he makes the point with some purple

passages. Let it go – he’s mostly

right on most of this, and it is good to be reminded.)

PERHAPS

THE MOST SIGNIFICANT PERSON OF THE ERA

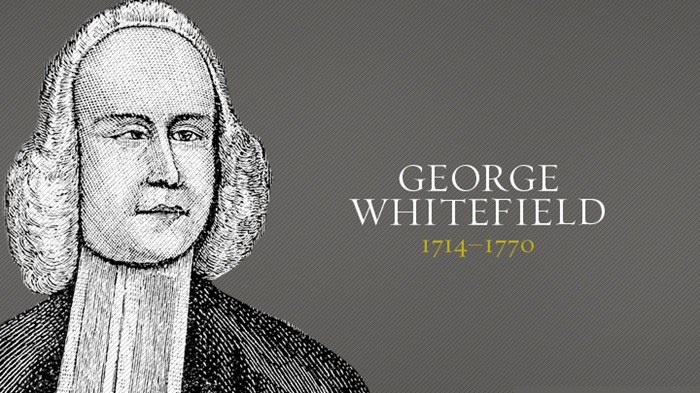

Some

readers may find a few chapters to seem incidental, but I hope not, as I

believe they are fully integral. There is a chapter, for instance, on George

Whitefield. I thought I knew a bit about him, but this was a spectacularly

interesting chapter. There are major historical biographies of the great

evangelist, but for most of us, this will give us a helpful picture of his

immense popularity in the colonies, and his unique friendship with Ben Franklin

(even though they differed considerably on religious matters.)

Whitefield

Whitefield

could speak out loud, outdoors of course, to up to 30,000 people — ever the

science guy, Ben Franklin measured it out. That up to 80% of the population of the colonies in the

mid-1700s had heard him preach is extraordinary. His sermons were published on the front page of the Pennsylvania Gazette. He was, in fact, what today we

would call a major celebrity. Metaxas may be overstating things (I don’t know)

but he insists that in many ways, Whitefield was one of the most important

persons in the whole founding of America.

He almost single-handedly spurred a great religious awakening (begun, of course, by the preaching of Jonathan Edwards a decade earlier) – creating

fertile ground upon which the new ideas of self-government and self-restraint

for the sake of the common good could flourish.

Whitefield’s own story, from poverty to Oxford, and his consequential concern for

the poor and the underclass (hence his unconventional outdoor preaching)

created an social ethos later called by historians democratization; that is, there was a populist sort of leveling –

all people of all classes and stations are equally loved as created by God, all

are equally guilty before God and all are equally redeemed by God in Christ. All had access to the throne-room of the

God of the universe, only a prayer away. He loved the native peoples, preached

to black settlements, and was respected by the rich and poor, the powerful and

the weak, the learned and the unschooled. The vivid revival preaching and renewal of faith promoted by

the Wesleys shaped the gifted Mr. Whitefield and his own tireless travels and

inspired speaking informed the North American continent in ways no one had

previously, ever.

THE

IMPORTANCE OF MORAL LEADERS

There

is a chapter in If You Can… that is ever and always important, one that helped clarify things

for me, called “The Importance of Moral Leaders.” He tells of a particular speech given by George Washington on

March 16, 1783 in the middle of a very dramatic part of the war. I was moved by

Metaxas’s telling of it, what he calls “Washington’s Finest Hour.”

Washington,

part way through the speech, “reached into his waistcoat pocket and pulled out

a pair of wire-rimmed spectacles. He had been using them for some time, but

never in front of his officers, so the gesture must have taken them aback. And

then came the famous line: ‘Gentlemen, you must pardon me. I have grown gray in

your service and now find myself growing blind.'”

With these words, the mood of the room changed

dramatically. There is no question that many of the angry, battle-hardened

officers had been softened and moved by his speech, but now, seeing their noble

leader in this unprecedented moment of weakness, they were undone. As

Washington read the congressman’s letter, many of them actually wept.

The

longer speech of Washington is filled with value-laden words, words Metaxas suggests

we do not hear much anymore, “sacred honor” and “dignity” and “glory” and such. I am not so sure that we do not hear

them – they are perhaps tossed around too often or too brazenly to mean much.

But I appreciate his concern, that we too often affirm leaders who are

pragmatists, or who seem to have know-how and skills, but are short of deep

virtue, both public and private. We need leaders of integrity, and we need to

be people who care about virtue and goodness and integrity.

Metaxas

writes, “One of the most fragile parts of our fragile system of ordered

liberties is the necessity of a basic trust between the people and their

leaders.”

I

recommend this chapter for careful consideration this election season. Methinks

even Mr. Metaxas and those he has on his radio show would benefit from a good

re-read. Can he make everybody read a chapter of his own book before their

interview? Maybe not.

Metaxas

deepens his good argument for leaders being those who can “make goodness

fashionable” by drawing on familiar ground for him, the wonderful and complex story

of William Wilberforce. This

section is thrilling and beautifully compelling. I am sure you will value it – and perhaps it will draw you

to read or re-read his earlier work on the great British parliamentarian who

fought to not only abolish the slave trade but to create a larger culture where

“morals and manners” were reformed.

ALMOST

CHOSEN PEOPLE

Perhaps

the thorniest chapter of the book is called “The Almost Chosen People” (a line

from Lincoln) on “American exceptionalism” which Mr. Metaxas admits is “rightly

controversial.”

Interestingly, it seems that the phrase itself comes from that nineteenth

century Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville, in his landmark book.

Metaxas

is clear that American exceptionalism “should have nothing to do with excesses

of nationalistic chest-beating and jingoistic hubris.” (“We may take some real

comfort,” he suggests, “in knowing it was in its first appearance a foreigner’s

cold-eyed analysis and subsequent wonderment at this country, when she was

young.”)

I

believe this stuff is complicated and it is a chapter with which I take

exception, as it isn’t exceptional enough. (Sorry, I couldn’t resist.)

I

would suggest you read it, perhaps even with a group, and think this through

for yourself. What a salon or coffee conversation you could have on any of

these chapters, but especially this one. (Maybe over some tea, in honor the

Brits, or some French wine, in honor of de Tocqueville.)

From

From

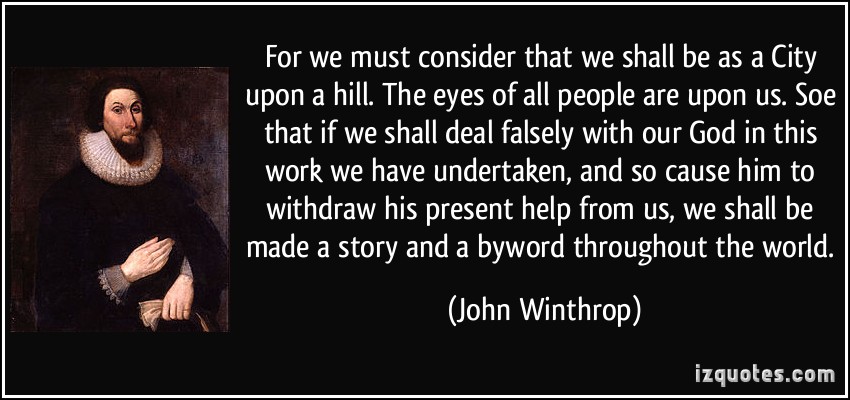

the summer of 1630 when a fleet of ships, including the Arbella, set sail from England, we have the story of John Winthrop

and the “shining city upon a hill” sermon. Metaxas says that Winthrop (the man

chosen to be the new Massachusetts Bay Colony governor) “was making clear to

them that what they were about to do was a tremendous burden, that they bore a

responsibility to all other peoples then living and to history – and to the

future.”

They

were not just, in Metaxas’s telling,

merely running from religious persecution, which

was considerable…but this trip was not merely about finding a place where they

might live their lives in peace. For them, living their lives in peace meant

they would have the opportunity to fulfill their responsibility to do something

important for God. They understood that freedom was not merely the freedom to

be left alone; it was the freedom to do what was right. Freedom was a gift from

God and they must use it for his purposes.

Metaxas insists,

This idea of freedom as something to be used in

the service of others is at the very heart of the Jewish and Christian

Scriptures; through Winthrop and the Puritans of Massachusetts it became an

important idea at the heart of the American project in the seventeenth century

and in the centuries after.

I

think this book, and even this chapter, is balanced and fair. Mostly. I wish he would have questioned

the too common misuse of the Bible’s references and promises to the covenant

people of ancient Israel applying them to any secular nation-state or people

group. That’s a hermeneutical matter for those who study the Bible, but utterly

germane when talking about God’s blessings upon any nation.

In this chapter of If You Can… there are lines that are grossly overstated, inexplicably

failing to omit the dark side of how the pilgrims and Puritans acted, the

mistreatment of indigenous peoples (perhaps in those years not as bad as some

think, and not nearly as evil as the great genocides committed by the Spanish

in Central and South America.) Metaxas is a scholar of the abolitionist

movement and outspoken about contemporary slavery today, so he is not

disinterested in the evils of injustice and racism, even those perpetrated in

those colonials years. To not name them, though, in the appropriate passages in

this chapter when he is talking about “the idea of living for others – of

showing them a new way of living – that was at the heart of America” is either disingenuous

or incredibly naïve. Either way, it’s bad.

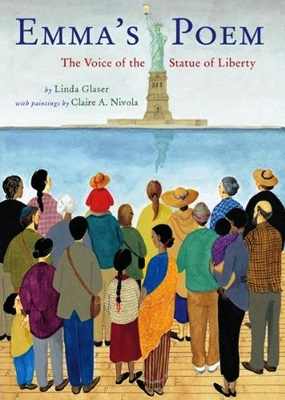

I love that

I love that

throughout the book (even on the cover) Metaxas is genuinely taken with the

spirit of Lady Liberty. He talks

about the great statue, and quotes at length the beautifully powerful poem by

the famous Emma Lazarus (“The New Colossus.”) For a strong conservative

pundit, he is surprisingly critical of those who are disinterested in the

plight of the immigrant and he waxes eloquent on the goodness of our general

openness to immigrants in our past. He tells of his own family’s rigorous

journey from Greece, and has  obvious reasons to be sympathetic to the cause of

obvious reasons to be sympathetic to the cause of

immigration. Yet, in his framing of this, as he offers a positive spin on

those who are anti-immigration, implying they aren’t that unreasonable or

uncaring. I scribbled in the margins, “One would wish. His naiveté is

breathtaking.” He then says “Very few are foolish enough to say that we don’t

want immigrants at all. They are widely considered to be our strength.” I wrote in the margins, “I wish!”

I suppose I should appreciate his optimism, but it struck me as almost willfully in denial about the harshness of some our fellow citizen’s attitudes these days. I know one person who said “I think it’s about time they took that statue down.” So, there’s that.

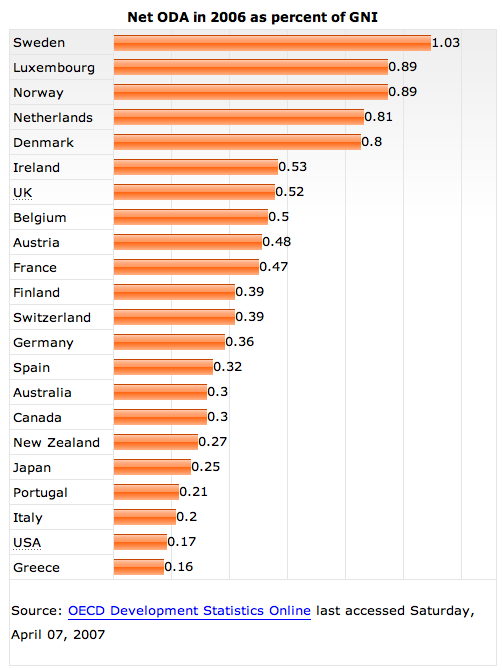

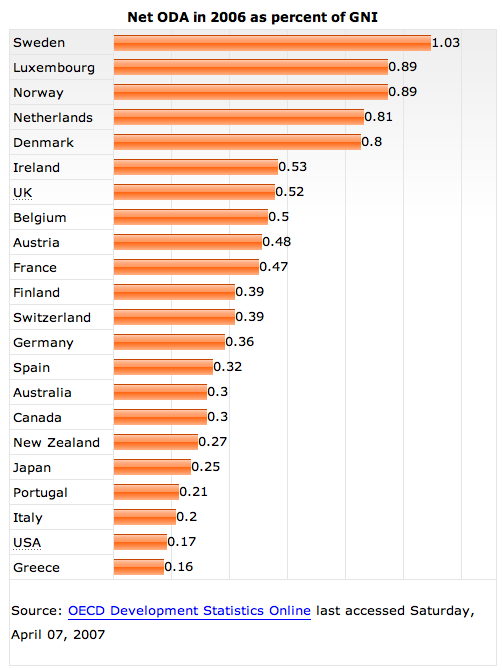

I

wondered who was fact-checking this portion, for instance when he says that

America has been “by a wide margin the most generous nation in the  world.” That statement is, as I thought nearly

world.” That statement is, as I thought nearly

everyone who studies such things knows, not so. If measured in terms of the percentage of our GNP going to

foreign aid, the United States is woefully low, with all sorts of countries

offering a much more generous portion of  their GDP to elevate world hunger and

their GDP to elevate world hunger and

the like. Yes, many Americans are

generous, and because we are wealthy, even a meager gift is a lot. I suppose it

is true that we are first in line to send medicine and the like, but, again,

this factoid about our generosity is glaringly wrong – we, as a nation, when

talking about foreign aid other than military aid – are woefully not generous. And

often, our foreign aid is tied to demands for policies which we craft, often

coercing capitulation (perhaps through the IMF, say, serving our business

interests.) Again, is Metaxas just ill-informed about these things? Is he not a

member of the citizens anti-hunger group Bread for the World or has he never

seen those charts listing our relative status compared to others, or hasn’t he

read Rich Christians in an Age of

Hunger which documents this so carefully? One would think his

editors, at least, would have caught that.

Still,

as I’ve said repeatedly, this is a fine book with remarkably interesting

stories, and much to ponder. There is stuff in here that I bet you’ve never

heard. For instance, if you haven’t

read Metaxas’ children’s story Squanto: A

Friend of Pilgrims you most likely don’t know his nearly unbelievable

Friend of Pilgrims you most likely don’t know his nearly unbelievable

story. He was called Squanto but

also Tisquantum. He had been

captured by Englishmen with evil intent in or around 1608, and taken to

England. He became a Christian and

years later returned to his native homeland in what we now call New England and

served as an interpreter; he played a major role in the famous Thanksgiving

drama of the pilgrims of the Mayflower

being taught to survive when he walked out of the woods to greet them in the spring

of 1621.

Squanto helped the Pilgrims establish a peace

with the local Native Americans that lasted fifty years, a stunning

accomplishment considering the troubles the settlers would have with native

tribes in the centuries following. Sadly, Squanto died not long after this, but

Bradford wrote that Squanto “desired the Governor to pray for him…Squanto even

bequeathed his possessions to the Pilgrims “as remembrances of his love.”

“It

is virtually impossible for us to fully appreciate today,” Metaxas observes,

how innovative the creating of this was, this drafting of the Constitution, and

how nearly it came to falling through. The men who struggled that long summer

to write it were themselves in deep disagreement and it is nearly miraculous

that they came to an agreement. (Alexander Hamilton, for instance, believed the

President and senators should be chosen for life, just as Supreme Court

justices are appointed for life.) From the remarkable Articles of Confederation

(written in six months near us here in York, PA, by the way) to the

ratification process, to the breathtaking drama of these brilliant thinkers

confined to Philadelphia then tasked with hammering out this brave new document

(including debates and compromises about slavery and slave holding states)

Metaxas describes it in such an interesting way, and helps us see why it

matters so much.

The

The

whole book is not exclusively about the founding fathers, as he spends

considerably time with Lincoln, including excerpting some of a speech given to

the New Jersey State Senate that is brilliantly worded, expressing “Lincoln’s

own sense of history and his place in it.” He ponders what Lincoln meant by

that evocative phrase “the mystic chords of memory.” He wonders how we can reform our own sense of God’s ways for

our land, and how we might appropriately and effectively share that with the

world.

He

critiques the contested idea of “Manifest Destiny” and he insists we have much

work to be done. He often mentions the sin of slavery – sounding like Lincoln,

at times, himself, struggling to help us see how we must become the sorts of

citizens and faithful people who love our land and resist its greatest

injustices and threats.

As

I said, I am not one who usually appreciates books calling us to be more patriotic,

to love America more, to get all cozy with what is often cheap sentiment or

theologically dangerous civil religion.

And this one, like others in that genre, has its blind spots and

misstatements. But it is generous,

it is interesting and enjoyable, it is mostly balanced. Importantly it reflects

on the meaning of love, of love of country, of the virtues of knowing what is

good to love. If You Can Keep It

invites us to not love our land “in exclusion to the goodness in other things.”

He warns against making our goodness a false idol which, he says, is actually

a posture which “hates real goodness.”

He

continues,

If we are loving what is properly good and true

and beautiful, we are ordering our affections against tribalism and jingoism;

we are ordering our affections so that they are in line with God’s affections,

because the selfishness of tribalism and nationalism are the very enemies of

what God loves.

Wow,

to overstate our own goodness can be idolatry! And to fail to honor the

goodness of Canada or Congo, Belgium or Bangladash, is “hating real goodness”?

I think that is what he means. Once we learn to love and honor  and value and

and value and

work for the good, true good, we will obviously care about our land, but we

will love the good elsewhere, as well.

As those who are committed to the habits of heart of a democracy, we

should be well-placed and well-equipped to be good global citizens. It is, in fact, a deep truth behind his

friend Os Guinness’s book applying these American principles of religious

toleration and deep pluralism to the global scale in a book called The Global

Public Square: Religious Freedom and the Making of a World Safe for Diversity. This illustrates a healthy way in which ideas and ideals from America’s own revolution can inform and shape ideas about how we can make peace in the complex global world of the twentyfirst century. It’s worth reading! And Metaxas would agree, I’m sure.

If You Can Keep It: The Forgotten Powers

of American Liberty proposes a sort of patriotism that seems right to me, and If You Can Keep It is a book inviting us

to live into that properly ordered, modest virtue of loving our nation well.

It isn’t perfect and most readers will find something to ponder, maybe something to contest. But I do think it is a very good read, and hope you consider it, for a book group, a study class, to send as a gift to someone who might need a bit of civic education, or to ponder yourself in this increasingly contested political season. Agree or not with all of Eric’s conclusions, I still think it is a good book, worthy of your twenty bucks. We’re happy to suggest it; add one from the following list, below, and you’ll be set for some holiday fire-works that matter.

FIVE MORE HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

Was America

Was America

Founded as a Christian Nation? A Historical Introduction

John Fea (Westminster/John Knox) $30.00

I have previously reviewed this highly regarded and significantly awarded book

and mention it from time to time here at BookNotes. I cannot say more clearly that this is a must-read for all of

us, at any time, but surely now when there is much public conversation about

this very topic. It would be a great supplement to Metaxas who is more

storyteller and American evangelist than trained historian. (By the way, Metaxas is not making a

claim that America is “a Christian country” the way some do, at least not in

his book about the virtues of American patriotism and the centrality of religious

freedom, If You Can Keep It. I do not mean to suggest Fea’s book is an alternative approach, as the two books have two different intentions.)

Dr. Fea has poured over countless primary

source documents, has spent his time at Mt. Vernon (where he has been a scholar

in residence) and has created a balanced and thoughtful book – “with a calm and

analytical clarity and profound knowledge” one reviewer said – that claries

much about the complex matter of religion and the founding fathers. This is a

conscientious and informed book, and his case studies of the faith and

religious practices of seven key founding fathers is the best stuff I’ve ever

seen on the topic.

American Exceptionalism

American Exceptionalism

and Civil Religion: Reassessing the History of an Idea John D. Wilsey (IVP Academic) $22.00

This is a major, recent work by a professor of history at Southwestern Baptist

Theological Seminary who has written widely on the evangelical critique of the

notion of a “Christian America.” There are numerous raves reviews by serious

historians and public intellectuals, such as this from Robert Tracy McKenzie, a

Wheaton College professor (and author of the excellent The First Thanksgiving) who says, “Any thinking Christian who

aspires to patriotism without idolatry would benefit from reading this fine

work.”

I

noted that I had some issues with Metaxas’s rendering of this topic in the

fascinating chapter in If You Can Keep

It. This would be a more scholarly, detailed study of the topic, and I

commend it to you.

Between Babel

Between Babel

and the Beast: America and Empires in Biblical Perspective Peter J. Leithart (Cascade Books) $24.00

This is a stunning bit of heavy scholarship and a powerful polemic in the

publisher’s “Theopolitical Visions” series. Listen to James K.A. Smith, who

writes,

When I read a critique of the heresy of

‘Americanism’ from someone who nonetheless ‘loves America,’ I take notice: this

is not the usual predictable boilerplate. In this important book, Leithart

brings his usual verve, erudition, and nuance to bear on one of the central

idolatries of our age.”

Or

listen to Princeton professor Eric Gregory:

Between Babel and Beast offers a bracing critique of American

political history and a pastoral call for repentance from imperial

‘Americanism.’ But Leithart’s distinctive analysis provides a more complex–and

potentially more constructive–biblical perspective on international politics

than can be found in the many ecclesial critics of empire. This crisply argued

and highly readable companion to Defending Constantine confirms that Leithart

is one of the most interesting voices in theology today.

God Of

God Of

Liberty: A Religious History of the American Revolution Thomas S. Kidd (Basic Books) $26.95 We

only have one of these gems left in hardback and aficionados of the

topic will want in their collection. Kidd is a well respected historian and a

Senior Fellow at an institute at Baylor University. The blurbs and reviews on

this volume are remarkable – impeccable scholars such as Rodney Stark and

Wilfred McClay, George Marsden and Mark Noll each offer fabulous

endorsements. Peter Lillback (a

popular author who writes about George Washington) says God of Liberty offers “an important critique of the mainstream

interpretations of the American Revolution…the surprising partnership of devout

believers and deistic doubters to secure America’s victory makes for

fascinating reading.”

The Christian Century’s review noted,

One of the many virtues of this book is that

Kidd is a careful and judicious historian… He points out–correctly–the

errors of both present-day secularists on the left, who insist that the

founders barred religious voices from political discourse, and the church-state

separation deniers on the right. The lesson of American history is that

although church and state are institutionally separate, morality and freedom

are seldom at odds and that, in fact, they are mutually reinforcing.”

Forgive Us: Confessions of a Compromised Faith edited by Elise Mae Cannon, Lisa Sharon

Forgive Us: Confessions of a Compromised Faith edited by Elise Mae Cannon, Lisa Sharon

Harper,Troy Jackson, Soong-Chan Rah (Zondervan) $22.99

I

do not think that Mr. Metaxas is unaware of the gross history of how even

church-leaders authorized and legitimized exceptional evil in our nation’s

history. The mistreatment of

Native peoples, blacks, immigrants and more are well documented and simply

essential to understand. Of course, he was not writing a history of our nation,

so it wasn’t in his purview to talk about the massacre of Indian peoples in the

1800s in the West or the abuse of Asian railway workers and the like. But he

was naming the goodness of our land, even arguing for an exceptional calling,

so it needed to be address.

I

understand that some think we have over-emphasized these injustices, and that

wallowing in past social sin erodes legitimate national pride and keeps us from

“moving on.” I protest. It is a weakness in Eric’s book that he didn’t name

more of these egregious sins (although he named some, and occasionally reminded us that

we should never minimize our nation’s faults and failings.) This book is a

counter-weight to cheap patriotism, a necessary reminder of the sad stuff of

our history and no celebration is legitimate without attending adequately to

this need for pubic confession and serous repentance. I applaud these brave

authors and this evangelical publisher for giving us this resource to know and

lament these tragic moments and awful patterns of our past.

As Metaxas says,

without vital virtue, the republic is doomed. Without repentance of these affronts to God and neighbor and

the earth itself, it could be argued our virtue is wanting. This book is a

must-read.

BookNotes

SPECIAL

DISCOUNTANY ITEM MENTIONED

20% off

order here

takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

just tell us what you want

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

just ask us what you want to know

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown, PA 17313 717-246-3333

Allow us to tell you about A Woman’s Place: A Christian

Allow us to tell you about A Woman’s Place: A Christian Ms. Beaty is a great reporter and writer (she is, by the

Ms. Beaty is a great reporter and writer (she is, by the I learned decades ago from a book that Beaty does not cite,

I learned decades ago from a book that Beaty does not cite,

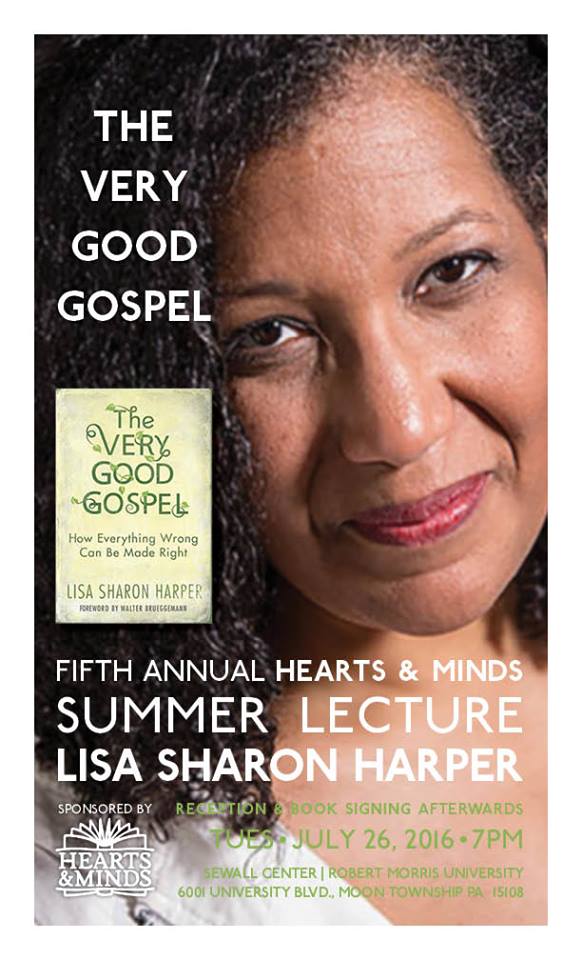

friend Lisa Sharon Harper at our Fifth Annual Hearts & Minds Pittsburgh Summer Lecture, Tuesday evening, July 26

friend Lisa Sharon Harper at our Fifth Annual Hearts & Minds Pittsburgh Summer Lecture, Tuesday evening, July 26

may enjoy knowing that Tim Keller’s Redeemer Presbyterian Church in NYC hosted him not long ago at an event where we were selling books — it was such fun to re-connect with him, talking with Milliken about Bob Long and Reid Carpenter and Mon Valley urban Young Life guys and reformational thinkers like Pete Steen.) In those years CCO introduced us to black leaders such as Bill Panell, Tom Skinner, Barbara Williams-Skinner, Carl Ellis, Elwood Ellis, John Perkins (whose connections in PIttsburgh even figures nicely in one of the biographies about him.)

may enjoy knowing that Tim Keller’s Redeemer Presbyterian Church in NYC hosted him not long ago at an event where we were selling books — it was such fun to re-connect with him, talking with Milliken about Bob Long and Reid Carpenter and Mon Valley urban Young Life guys and reformational thinkers like Pete Steen.) In those years CCO introduced us to black leaders such as Bill Panell, Tom Skinner, Barbara Williams-Skinner, Carl Ellis, Elwood Ellis, John Perkins (whose connections in PIttsburgh even figures nicely in one of the biographies about him.)

salt and light and leaven, as Jesus Himself put it. We are to seek first God’s reign, Christ’s Kingdom, His glory. There is much wrong with the world to which we must say “no!” (Perhaps you recall the long review I did recently of the challenging new book by Os Guinness called Impossible People: Christian Courage and the Struggle for the Soul of Civilization; he helps us think this through in necessarily serious ways.) And there is much good, or course, to which we may say “yes!”

salt and light and leaven, as Jesus Himself put it. We are to seek first God’s reign, Christ’s Kingdom, His glory. There is much wrong with the world to which we must say “no!” (Perhaps you recall the long review I did recently of the challenging new book by Os Guinness called Impossible People: Christian Courage and the Struggle for the Soul of Civilization; he helps us think this through in necessarily serious ways.) And there is much good, or course, to which we may say “yes!” As C. Christopher Smith argues in Reading for the Common Good: How Books Help Our Churches and Neighborhoods Flourish books can be transforming for us as we slow down, think about important things, take in new ideas, allowing the cadences and insights to shape us as we form bonds that reading together can create.

As C. Christopher Smith argues in Reading for the Common Good: How Books Help Our Churches and Neighborhoods Flourish books can be transforming for us as we slow down, think about important things, take in new ideas, allowing the cadences and insights to shape us as we form bonds that reading together can create.

and provoke us to deep conversations about “what God’s people should do.”

and provoke us to deep conversations about “what God’s people should do.”

because of their meager message – au contraire – but because they are short. Jewish readers call all of them together The Book of the Twelve. I could start off talking about how studying Amos in college rocked my world, how seeing verses like Micah 6:8 drawn in early 70s calligraphy spoke to me, about how just last week I got to introduce young Christians to Isaiah 58. I’d say how years ago Walter Brueggemann’s Prophetic Imagination became so vital for so many of us., Walsh, too. I like that line from Malcolm Boyd, saying that often in church groups we study the prophets but we wouldn’t know one if one sat down next to us. He’s right, I’m afraid, about our general lack of prophetic discernment, but he’s mostly wrong that we study the prophets. I could start there.

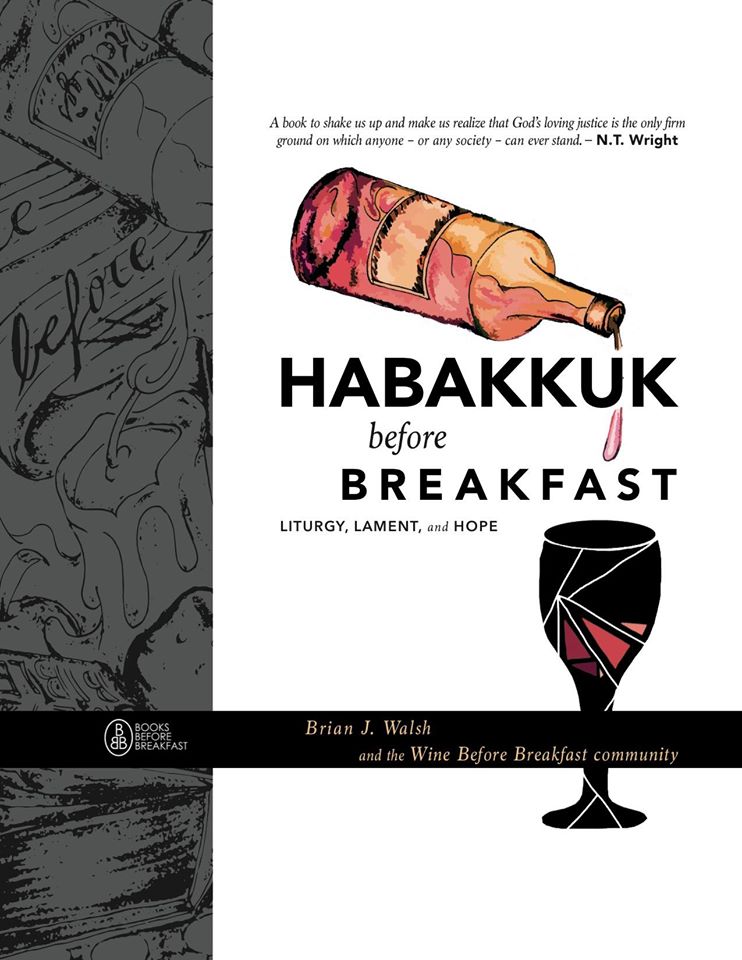

because of their meager message – au contraire – but because they are short. Jewish readers call all of them together The Book of the Twelve. I could start off talking about how studying Amos in college rocked my world, how seeing verses like Micah 6:8 drawn in early 70s calligraphy spoke to me, about how just last week I got to introduce young Christians to Isaiah 58. I’d say how years ago Walter Brueggemann’s Prophetic Imagination became so vital for so many of us., Walsh, too. I like that line from Malcolm Boyd, saying that often in church groups we study the prophets but we wouldn’t know one if one sat down next to us. He’s right, I’m afraid, about our general lack of prophetic discernment, but he’s mostly wrong that we study the prophets. I could start there. The cover of Habakkuk Before Breakfast shows a portion of a painting done by a First Nations artist who hung around the University of Toronto Wine Before Breakfast community, to whom the book is dedicated. Gregory “Iggy” Spoon died as the sermons and prayers and liturgies and reflections that became this book were being prepared and experienced. I recall reading a message from Brian about their pain and lament and anguish upon Iggy’s unexpected death in March 2015. Iggy’s death impacted their community (as did a few other deaths and tragedies that season) and Brian and the WBB community honored him as they mourned their loss. As the Hebrew prophet three millennia ago railed about a pious religious establishment that seemed to have little room for humility and care for the outsider, Iggy stood in their midst as a suffering brother, with gifts and goodness and insight and pain, like anyone, but with a past that seemed to make evident, I gather, much that is wrong with a formal religion that doesn’t understand hospitality, inclusion, or justice. Mostly, I guess, he was a beloved friend.

The cover of Habakkuk Before Breakfast shows a portion of a painting done by a First Nations artist who hung around the University of Toronto Wine Before Breakfast community, to whom the book is dedicated. Gregory “Iggy” Spoon died as the sermons and prayers and liturgies and reflections that became this book were being prepared and experienced. I recall reading a message from Brian about their pain and lament and anguish upon Iggy’s unexpected death in March 2015. Iggy’s death impacted their community (as did a few other deaths and tragedies that season) and Brian and the WBB community honored him as they mourned their loss. As the Hebrew prophet three millennia ago railed about a pious religious establishment that seemed to have little room for humility and care for the outsider, Iggy stood in their midst as a suffering brother, with gifts and goodness and insight and pain, like anyone, but with a past that seemed to make evident, I gather, much that is wrong with a formal religion that doesn’t understand hospitality, inclusion, or justice. Mostly, I guess, he was a beloved friend.

Colossians Remixed: Subverting the Empire Brian J. Walsh & Sylvia C. Keesmaat (IVP Academic) $24.00 I’ve mentioned this above, indicating it shows mature Scriptural scholarship applied in exceptionally serious ways. I thought I should list it here. This really is an audacious, brilliant bit of work, with more than one viewpoint offered as a conversation occurs on the meaning of the text and as they bring the early church experiences to us in creative storytelling and powerful cultural analysis. This is solid Biblical exegesis, a specific book studied not only in it’s own context, but within it’s own place in the unfolding redemptive plan revealed in Scripture. They see echos of the Old in this letter of Paul’s and they see within the struggles of these early Christ-followers hints of how we can live out our faith today. Endorsements include rave reviews from Tom Wright, Marva Dawn, Andrew Lincoln, Walt Brueggemann, Frank Thielman and other top notch Biblical scholars. And some bookseller guy from Dallastown who’s stuck in there raving among the big names. I still love this book and highly recommend it — hold on to your hat, though. Colossians Remixed will challenge how you read the Bible, how you think about discipleship and church, and how you see the world.

Colossians Remixed: Subverting the Empire Brian J. Walsh & Sylvia C. Keesmaat (IVP Academic) $24.00 I’ve mentioned this above, indicating it shows mature Scriptural scholarship applied in exceptionally serious ways. I thought I should list it here. This really is an audacious, brilliant bit of work, with more than one viewpoint offered as a conversation occurs on the meaning of the text and as they bring the early church experiences to us in creative storytelling and powerful cultural analysis. This is solid Biblical exegesis, a specific book studied not only in it’s own context, but within it’s own place in the unfolding redemptive plan revealed in Scripture. They see echos of the Old in this letter of Paul’s and they see within the struggles of these early Christ-followers hints of how we can live out our faith today. Endorsements include rave reviews from Tom Wright, Marva Dawn, Andrew Lincoln, Walt Brueggemann, Frank Thielman and other top notch Biblical scholars. And some bookseller guy from Dallastown who’s stuck in there raving among the big names. I still love this book and highly recommend it — hold on to your hat, though. Colossians Remixed will challenge how you read the Bible, how you think about discipleship and church, and how you see the world.  Prophetic Lament: A Call for Justice in Troubled Times Soong-Chan Rah (IVP) $17.00 I have mentioned this often; it is a lively and moving commentary on the Old Testament book of Lamentations. If you resonate with Habakkuk’s call to big picture stuff, global concerns, justice and our corporate brokenness, this could be really useful. If you like the way Walsh weave lament into his sermons about justice and hope, then you will realize the value in this sort of prophetic imagination, shaped by the Word and by modern day injustices. We need books like this, for sure.

Prophetic Lament: A Call for Justice in Troubled Times Soong-Chan Rah (IVP) $17.00 I have mentioned this often; it is a lively and moving commentary on the Old Testament book of Lamentations. If you resonate with Habakkuk’s call to big picture stuff, global concerns, justice and our corporate brokenness, this could be really useful. If you like the way Walsh weave lament into his sermons about justice and hope, then you will realize the value in this sort of prophetic imagination, shaped by the Word and by modern day injustices. We need books like this, for sure.  Reality, Grief, Hope Walter Brueggemann (WJK) $15.00 This is, in many ways, the book decades in the making, a simple and passionate follow up to The Prophetic Imagination. Like Walsh, Brueggemann highlights lament, drawing on the prophets own denunciation of ancient Israel, calling a remnant community to stand in covenantal fidelity, seeing thinks as God does, even if it puts us at odds with church and state. Brueggemann does really help us see that what happened in 587 BCE is somehow generative for us now, after 9-11 and with the collapse of so many ways of doing things. This is a great little book.

Reality, Grief, Hope Walter Brueggemann (WJK) $15.00 This is, in many ways, the book decades in the making, a simple and passionate follow up to The Prophetic Imagination. Like Walsh, Brueggemann highlights lament, drawing on the prophets own denunciation of ancient Israel, calling a remnant community to stand in covenantal fidelity, seeing thinks as God does, even if it puts us at odds with church and state. Brueggemann does really help us see that what happened in 587 BCE is somehow generative for us now, after 9-11 and with the collapse of so many ways of doing things. This is a great little book. Saving the Bible From Ourselves: Learning to Read and Live the Bible Well Glenn R. Paauw (IVP) $18.00 I am quite taken with this and can’t wait to really dive in. Each chapter explains a posture or tendency that we have to make the Bible harder than it needs to be, or more confusing, or readings that are prone to cause us to miss the meaning of the text. For each error, Paauw gives an alternative approach, fresh ways to save the Bible — not because the Bible needs saving, but because we’ve learned bad habits of reading it wrongly. I get it. This is good, good stuff. Endorsements on the back from Walter Brueggemann He calls it “puckish” but series. Another endorsement rings out from Mark Noll.

Saving the Bible From Ourselves: Learning to Read and Live the Bible Well Glenn R. Paauw (IVP) $18.00 I am quite taken with this and can’t wait to really dive in. Each chapter explains a posture or tendency that we have to make the Bible harder than it needs to be, or more confusing, or readings that are prone to cause us to miss the meaning of the text. For each error, Paauw gives an alternative approach, fresh ways to save the Bible — not because the Bible needs saving, but because we’ve learned bad habits of reading it wrongly. I get it. This is good, good stuff. Endorsements on the back from Walter Brueggemann He calls it “puckish” but series. Another endorsement rings out from Mark Noll. Free for All: Rediscovering the Bible in Community Tim Condor & Daniel Rhodes (Baker) $16.99 This was a splendid, generative book that came out of the “emergent village” imprint a number of years ago. It’s out of print but we have a few left. I know Walsh liked it — it’s main point being that we must unleash the Scriptures among us, allow us all to share our thoughts, and struggle hard for a fair and communal reflection on the meaning of it all. I think this is a strong resource, for those who understand that we need a communal reading and interpretation of Scripture and for those who have been hurt by more didactic and authoritarian teaching. It seemed right to name it here. It had been rigorously endorsed with nice blurbs from Walsh, Will Willimon, Stanley Hauerwas, Phylllis TIckle, and John Franke.

Free for All: Rediscovering the Bible in Community Tim Condor & Daniel Rhodes (Baker) $16.99 This was a splendid, generative book that came out of the “emergent village” imprint a number of years ago. It’s out of print but we have a few left. I know Walsh liked it — it’s main point being that we must unleash the Scriptures among us, allow us all to share our thoughts, and struggle hard for a fair and communal reflection on the meaning of it all. I think this is a strong resource, for those who understand that we need a communal reading and interpretation of Scripture and for those who have been hurt by more didactic and authoritarian teaching. It seemed right to name it here. It had been rigorously endorsed with nice blurbs from Walsh, Will Willimon, Stanley Hauerwas, Phylllis TIckle, and John Franke. Called to Community: The Life Jesus Wants for H

Called to Community: The Life Jesus Wants for H

Slow Church: Cultivating Community in the Patient Way of Jesus C Christopher Smith & John Pattison (VIP) $17.00 I have said over and over that this is one of the most significant books on the church I’ve read in decades. It brings a Walsh-like critique to the idols and ideologies of growth and status and efficiency and invites us to slow down, build community, learn patience and through God’s grace, gather a human-scale sort of missional energy for our own neighborhoods. Learning a sense of place, having an eye for injustice, but enjoying the good things in our areas is all part of what it means to be followers of Jesus in a slower church. There’s a good study guide for it, now, too.

Slow Church: Cultivating Community in the Patient Way of Jesus C Christopher Smith & John Pattison (VIP) $17.00 I have said over and over that this is one of the most significant books on the church I’ve read in decades. It brings a Walsh-like critique to the idols and ideologies of growth and status and efficiency and invites us to slow down, build community, learn patience and through God’s grace, gather a human-scale sort of missional energy for our own neighborhoods. Learning a sense of place, having an eye for injustice, but enjoying the good things in our areas is all part of what it means to be followers of Jesus in a slower church. There’s a good study guide for it, now, too.  Subversive Jesus: An Adventure in Justice, Mercy & Faithfulness in a Broken World Craig Greenfield (Zondervan) $15.99 I wasn’t sure this was going to be all that profound — the word “subversive” is over-used and not every hip book about doing cool justice work is that good — until an old CCO friend told me they knew this guy and assured me he was doing great work, and that we’d love his forthcoming book. And, wow, what a book — I could hardly put it down. It is conversational but mature, and he is obviously involved in doing inspiring work. And Greenfield has some fun, too. His antics protesting cruise ship injustices by getting a group to dress like pirates was hilarious — sort of a cross between Shane Claiborne and Bob Goff. (And they didn’t just act up once, but entered into longer-term relationships with third world workers on these ships who are terribly abused. Who knew?)

Subversive Jesus: An Adventure in Justice, Mercy & Faithfulness in a Broken World Craig Greenfield (Zondervan) $15.99 I wasn’t sure this was going to be all that profound — the word “subversive” is over-used and not every hip book about doing cool justice work is that good — until an old CCO friend told me they knew this guy and assured me he was doing great work, and that we’d love his forthcoming book. And, wow, what a book — I could hardly put it down. It is conversational but mature, and he is obviously involved in doing inspiring work. And Greenfield has some fun, too. His antics protesting cruise ship injustices by getting a group to dress like pirates was hilarious — sort of a cross between Shane Claiborne and Bob Goff. (And they didn’t just act up once, but entered into longer-term relationships with third world workers on these ships who are terribly abused. Who knew?)

know his great pair of recent paperbacks,

know his great pair of recent paperbacks,

The Secret of Their Greatness and

The Secret of Their Greatness and

obvious reasons to be sympathetic to the cause of

obvious reasons to be sympathetic to the cause of world.”

world.” their GDP to elevate world hunger and

their GDP to elevate world hunger and Friend of Pilgrims you most likely don’t know his nearly unbelievable

Friend of Pilgrims you most likely don’t know his nearly unbelievable

and value and

and value and Was America

Was America